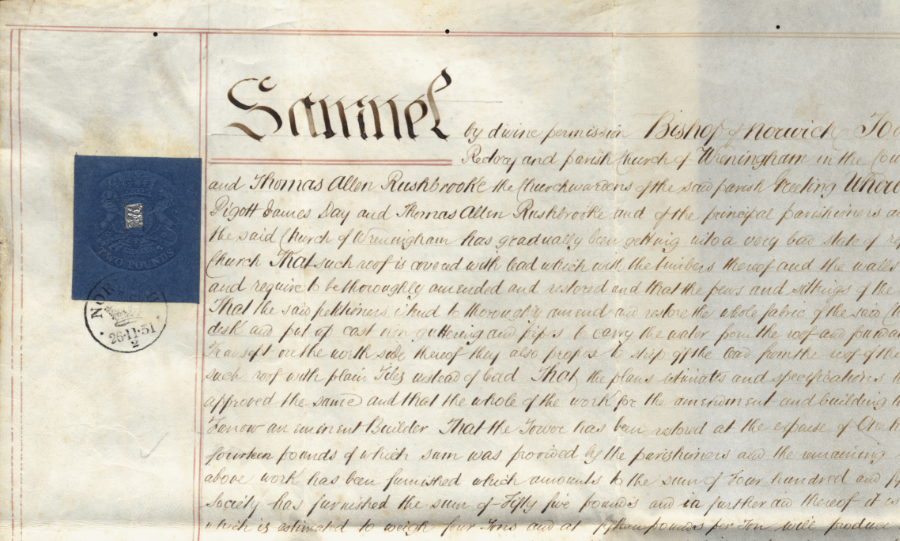

Modern commentators tell us that the top two-thirds of the Wreningham church tower collapsed in 1852 and was rebuilt the following year at about the same time the North Transept was added to the church. That timeline appears to be at odds with the “faculty” document which was written at the time. A faculty is a legal document issued by the Diocese giving approval for works to be carried out.

Faculties are preceded by “petitions” which provide the initial (formal) request from a church to carry out work or make changes on its property. The petition, in this case, had been prepared by the rector: Rev John Pigott and his churchwardens: James Day and Thomas Allen Rushbrooke. A petition needs to provide sufficient information, evidence and justification to enable a decision to be taken. Where expenditure is involved, that aspect also needs to be addressed. Two different subjects appear to have been included in this petition.

The first related to the reconstruction of the fallen tower; the second related to the building of a North Transept to seat additional parishioners within the building.

In the faculty, the section of narrative about the tower tells us, when it fell, it did “considerable injury to the roof of the Church”. We might imagine many tons of stone spreading out in all directions. The four bells in their frame must have also ended up in the resulting mess. Fortunately, no-one was standing in the way!

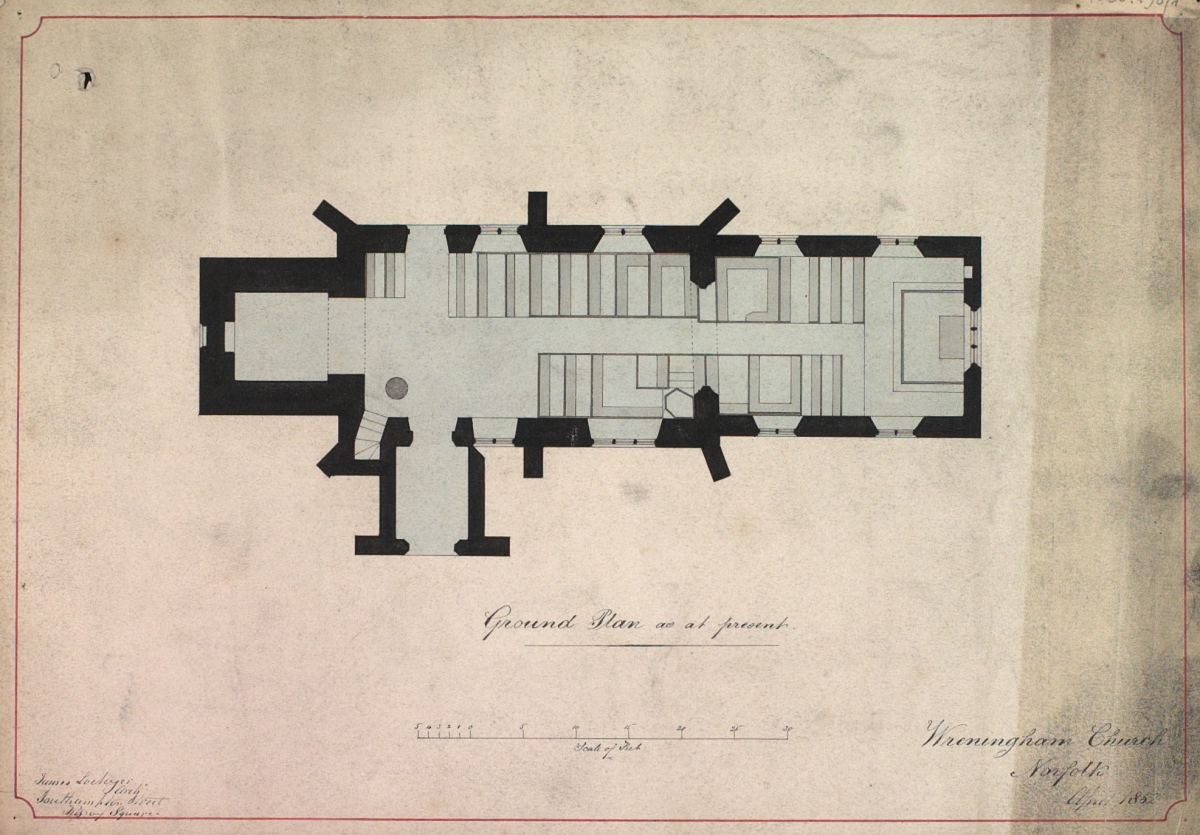

The October 1852 faculty went into detail about the tower and also stated that the tower had already been reconstructed at a cost of £151 2s 6d – of which £114 was “paid by the parishioners” and the remainder “by subscription”. There is architect James Lockyer’s drawing of Wreningham Church, now in the Lambeth Palace Library dated April 1852 confirming the tower reconstructed is (already) complete. As the reconstruction of the tower would have been a big job, and lime mortar can’t be laid in winter, it is only reasonable to assume the tower must have fallen and been reconstruction in the previous year: 1851 – not 1852 as is generally stated. We might also presume James Lockyer’s April 1852 drawing showing the completed tower was created to supported the petition – suggesting the petition might have been lodged in, say, mid-1852.

So where is the earlier faculty to approve the reconstruction work on the tower? Perhaps there wasn’t one? (The Norfolk Record Office catalogue of church faculties suggests that correct procedures had not always been followed from the late 1700s and during the first half of the 1800s.) In view of the level of detail given in this faculty, was this document also intended to provide a retrospective approval for the tower’s reconstruction?

Let us move onto the second part of the faculty which relates to the North Transept:

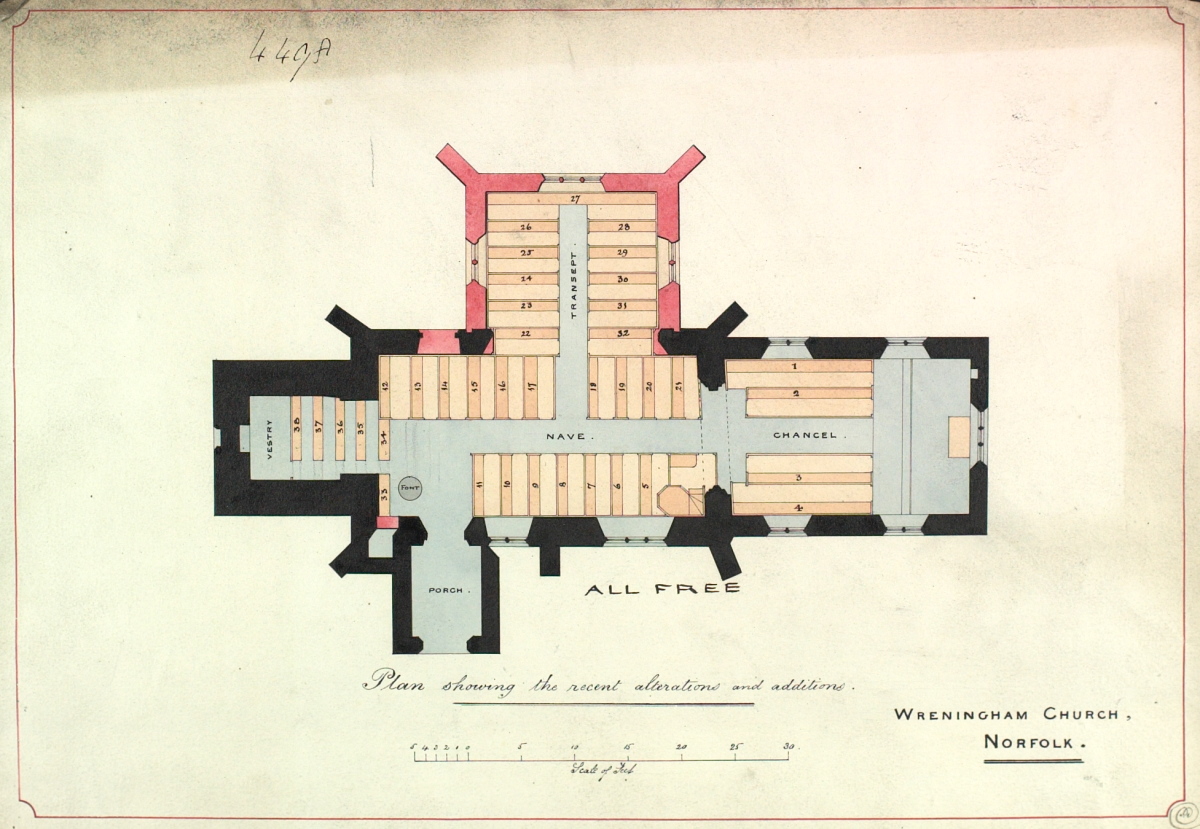

Perhaps this drawing was initially created as part of the “specification” for the new works? This Image is also Courtesy of Lambeth Palace Library ref: ICBS04498

In the faculty, the North Transept work was estimated to cost £450. An “eminent builder”, Mr Thomas Farrow was named as the man who was going to do the work and he had already put his signature to the petition accepting the accuracy of its information. (Had Thomas Farrow, believed from Diss, been involved in the earlier tower reconstruction?)

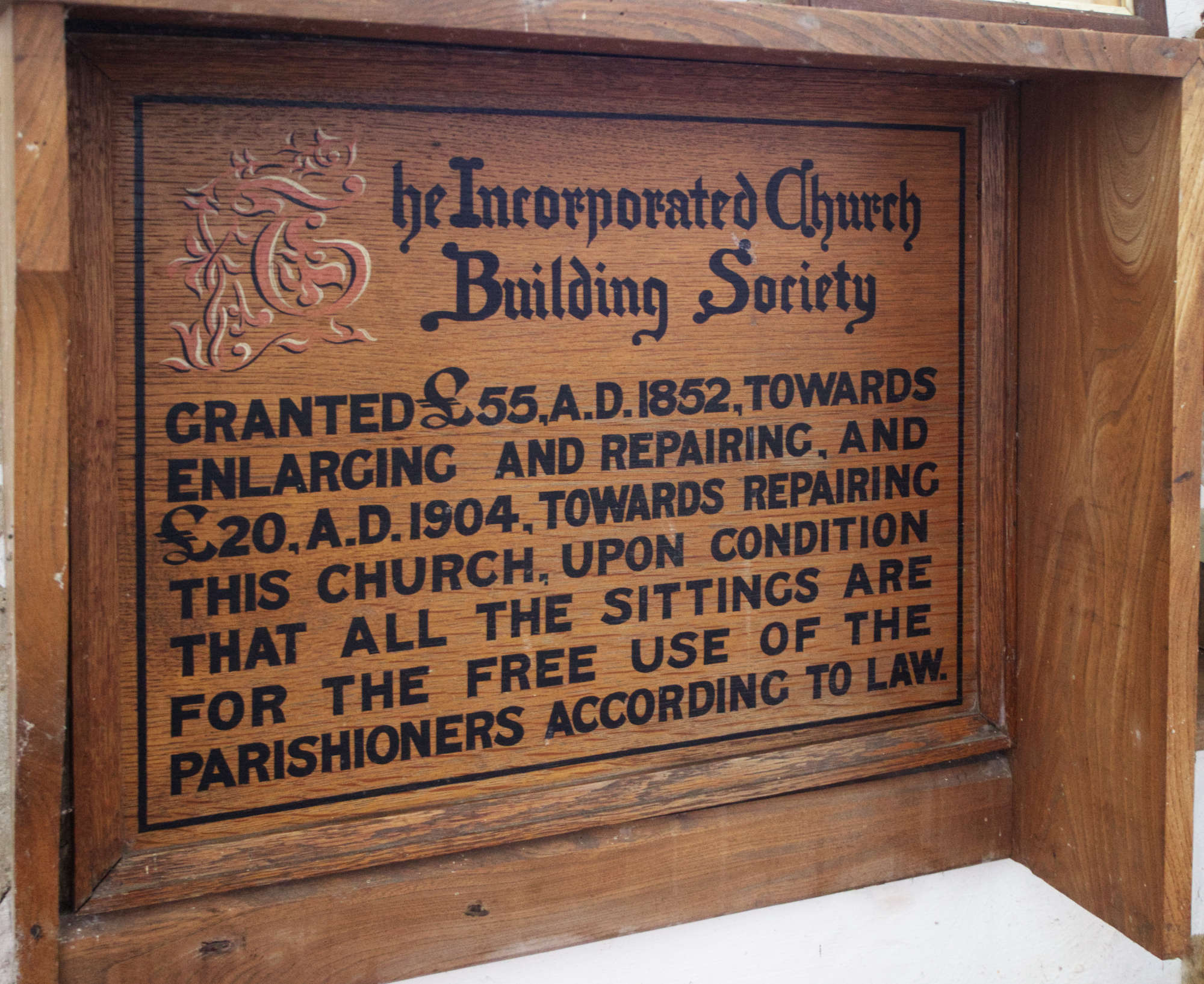

The approved plan was to sell the lead from church roof over the nave and replace it with tiles – which were cheaper. This would raise £60 of the required money. £50 had also been promised by the Church Building Society. The faculty did not identify how the balance might be paid.

Following the receipt from the Church Building Society of £50 in 1852 and a futher £20 in 1904, a wooden plaque was fixed to the wall at the base of the tower.

The text set out the terms for the gifts: being on condition that the extra “sittings” (resulting from the construction of the north transept etc) would be for free to use by the parishioners.

The faculty specifically states (perhaps repeating words from the petition?) that additional work should include cast iron gutters and water pipes to take water away from the church. Is there an inference that some of the issues requiring rectification might have been due to historical water damage?

The petition had also stated that the “Church of Wreningham has gradually been getting into a very bad state of repair” and “the walls windows floors pews and sittings” and “require to be thoroughly amended and restored”. Was this an implied criticism of the previous rector – the Rev Wilson, who had only recently departed?

The Bishop of Norwich signed the faculty on 6th October 1852.

The architect named on the April 1852 drawings of the reconstructed tower and the original ground plan of the church is James Lockyer. The career of James Lockyer – actually: James Morant Lockyer, was summarised in a copy of the “The Builder”– details courtesy of a Professor Donaldson, published on 19th November 1915. It describes how James Morant Lockyer had trained in the offices of Thomas Little, travelled extensively – particularly to Italy and, on his return to England, had inherited his father’s architectural practice.

The work at Wreningham appears to have been one of his earliest commissions when he was still in his late 20s.

The above linked article describes the Wreningham work including the (rebuilt) church tower and also the “Parsonage house” (which we take to mean the Rectory in Church Road – being constructed at the same time). Although not named in the faculty as the architect responsible for the North Transept – and no name appears on that drawing, that doesn’t mean he didn’t do it. The page style is very similar to the other two Wreningham drawings in Lambeth Palace’s bundle of three. Perhaps the North Transept plan was drawn up by an assistant? Confusingly, Lambeth Palace appear to have attributed the Wreningham church drawings to James’s father – also called James Lockyer, and have listed his father’s dates of birth and death within their catalogue.

James Morant Lockyer died at the very young age of 41. His most significant work was the design of the Heal & Son shop in Tottenham Court Road, London, which is both desribed and illustrated in the above linked article. It was especially well known for its shop-front and arcade styling although the original shop has not survived. A photograph of James Morant Lockyer is held at the National Portrait Gallery. Sadly, he ended his days totally blind and living in a lunatic asylum.

Possible Time-line

Top of church tower collapses, say, in 1851.

Reconstruction of tower is undertaken during 1851 – but is certainly complete by April 1852. At the same time, a plan has been developed to enlarge the church and make improvements. The plan is to cover part of the cost of this new work (estimated at £450) from the sale of lead covering the nave roof – estimated to weigh 4 tons and to be replaced by roofing tiles.

The faculty states that the petition has been developed by the (new and interim) Rector (Rev John Robert Piggot) and the churchwardens (James Day and Thomas Allen Rushbrooke). It seems very likely the petition would have included at least two of the three architect’s drawings – two of which are dated April 1852 – so the petition might have been lodged with the Diocese in about mid-1852.

The Diocese investigates the petition, and the faculty is granted in October 1852 so that work can get underway.

What happened next

The faculty tells us the new works will be undertaken by builder, Mr Thomas Farrow. However, there is no reference in the faculty about how the £340 balance would be funded or how Mr Farrow will be paid for the majority of the work.

The church history booklet states that Rev Piggot arrived in 1851 (taking over from Rev Robert Wilson). However, at about the same time the faculty was granted, the Rev Piggot – who appears to have had an interim role, moves on as the Rev Upcher has just been appointed.

The Rev Piggot had already instigated the construction of a new Rectory. County Directories suggest the cost of the Rectory construction was £1,600. That appears to be an enormous sum of money – especially when the land on which it would be built was already provided. Did this large sum include the £340 balance to build the North Transept and did all/most of it come from the pocket of the incoming Rev Upcher? Unless we find evidence, we will never know.

We should note that the Rev Upcher was a very wealthy man and also the grandson of the Lord of the Manor – the post of rector was in the gift of the manor. Perhaps the Lord of the Manor was a key player in the “problem solving” aspect for this entire story?