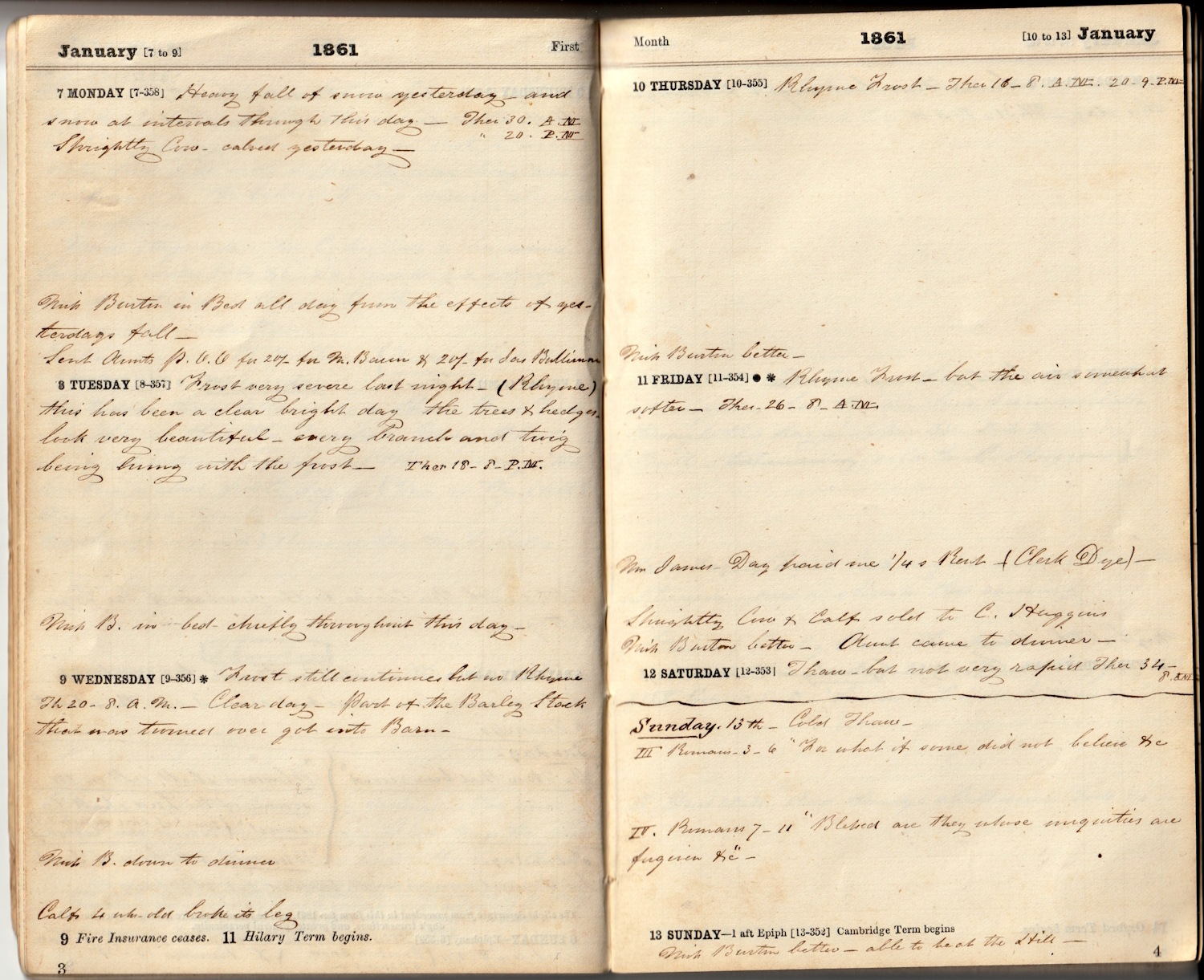

In 1861, John William Bullimore kept a day-by-day diary for the whole year. The diary is still with us, today, and provides an enormous insight into his life and times. It has now been transcribed and a link to a pdf copy is provided here.

Further information information about the diary’s contents is provided below to help readers of the linked text follow the many different entries and themes.

Background

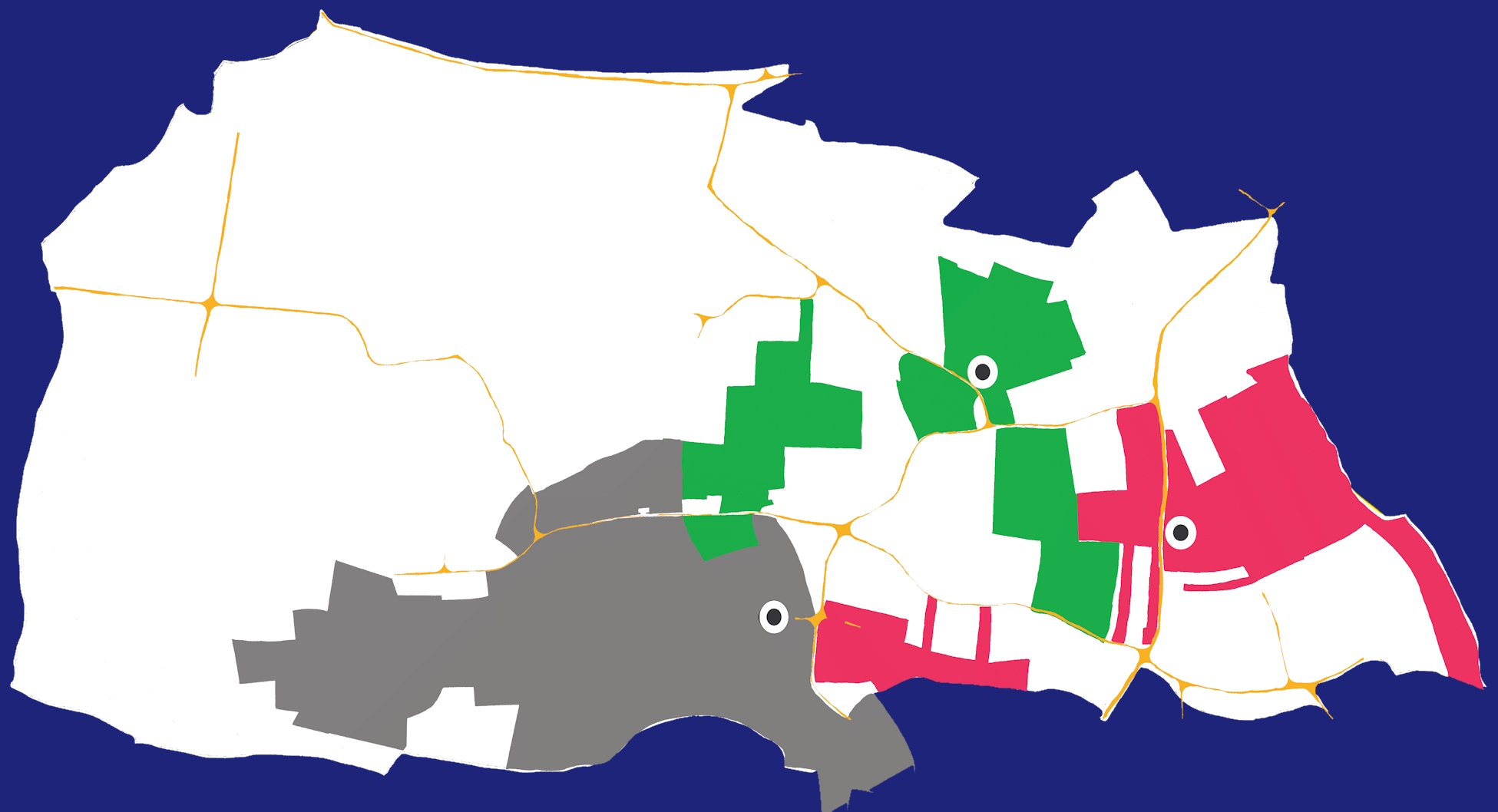

John Bullimore was, primarily, a farmer: his recorded information covers many aspects of the farming year. At the time, he was managing about 480 acres of land on behalf of his employer, Maria Burton. This amounted to just over one quarter of the entire parish and his responsibilities included the activities on 3 farms: Burton’s Farm, Elm Tree Farm (then known as George’s Farm) and Hill Farm. The Census for 1861 shows that he was controlling 20 men and 6 boys. In the diary we can follow much of the animal husbandry together with the crop planting and the frenetic pace of the harvest.

Burtons Farm (plan c1869) shown in grey. Maria Burton was the tenant.

Hill Farm (plan c1838) shown in red. Maria Burton was the owner.

George’s/Elm Tree Farm (plan c1838) in green. Maria Burton was the owner.

The 3 farmhouses are illustrated as black & white “doughnuts”.

In the diary, we see that John Bullimore describes Burton’s Farm as the “House” – it’s where he lived during that period. He refers to the other two farm locations as the “Hill” – probably because they are both on generally higher ground.

The diary also describes aspects of John Bullimore’s personal life and his many other village activities. The latter include his involvement with tax collection and other official parish duties.

In January 1861, he had just celebrated his 34th birthday yet, even at this young age, he was already involved in helping villagers draw up their Wills – something that he was going to be doing much more of in the coming years. In due course, he also became an executor in many Wills and a supervisor of at least one family trust.

The diary describes visits by his family members living in different parts of Norfolk; in 1861, his only relative who was resident in Wreningham was his aunt, Barbara Denny.

Here is a photograph from the period – possibly taken in early 1858 because we have a record from John Bullimore’s Pocket Book which lists him paying 5 shillings for a photograph, that year – a significant amount of money, at the time.

We are confident the man in the photograph is John Bullimore.

The Victorians were always keen on family photos. Hence, it is very possible the younger lady on the right is his sister, Anna – who (then) lived in Norwich. If that is correct, we might expect the lady in the centre to be his aunt: Barbara Denny. In 1854, Barbara Denny had beome a widow. She had moved to Wreningham from Heckingham (near Loddon) sometime after that.

The Weather

As a farmer, John Bullimore’s livelihood was inevitably impacted by the vagaries of the weather. Almost every day’s diary entry includes a description of the weather – although not always using the correct/modern-day spellings! Whilst the weather helped with some tasks it hindered in many others – his occasional frustrations are plain to see.

January 1861 commenced with nearly one month of frost and snow. This had followed about two weeks of similar weather during the previous month. It gave him serious challenges in how to deploy his many farm workers.

Saturdays and Sundays

The diary shows that, during 1861, it was quite common for John Bullimore to spend Saturdays in Norwich. Sometimes this was to conduct farm business – for example: selling grain. He also visited family members and occasionally conveyed friends or family members on his journeys between Wreningham and Norwich.

Sundays were always a day of rest and John Bullimore appears to have given over his Sundays to religious activities. The latter have not yet been transcribed from the diary. [They will be included elsewhere on this website, in due couse.]

The 1861 Census

Saturday 8th April 1861 was Census Day. Although John Bullimore was involved in many aspects of village life, the Census was not one of those. A transcription of the full results of Wreningham’s 1861 census can be found here. In summary, for two of the above three farms:

At Burton’s Farm – a large property, we can find: Maria Burton (Head) – described as “Mary” in the Census; John Bullimore the (Farm) Steward; Elizabeth Hare – a married lady but without her husband; servant: Elizabeth Goodrum and groom: George Moore.

John Bullimore’s aunt, Barbara Denny – a widow, lived at Hill Farm, along with a servant: Clara Head and lodger Charles Copeman. Charles Copeman was a “carter” – the 1800s equivalent of “a man with a van”! In the diary, on 16th October, we see that Charles Copeman had just moved out of his accommodation at Hill Farm: this was just a few weeks after the death of his farm labourer father: Edward Copeman. Edward Copeman, who had lived just a couple of doors from Burton’s farmhouse, in Ashwellthorpe Road, may well have been one of John Bullimore’s farmhands.

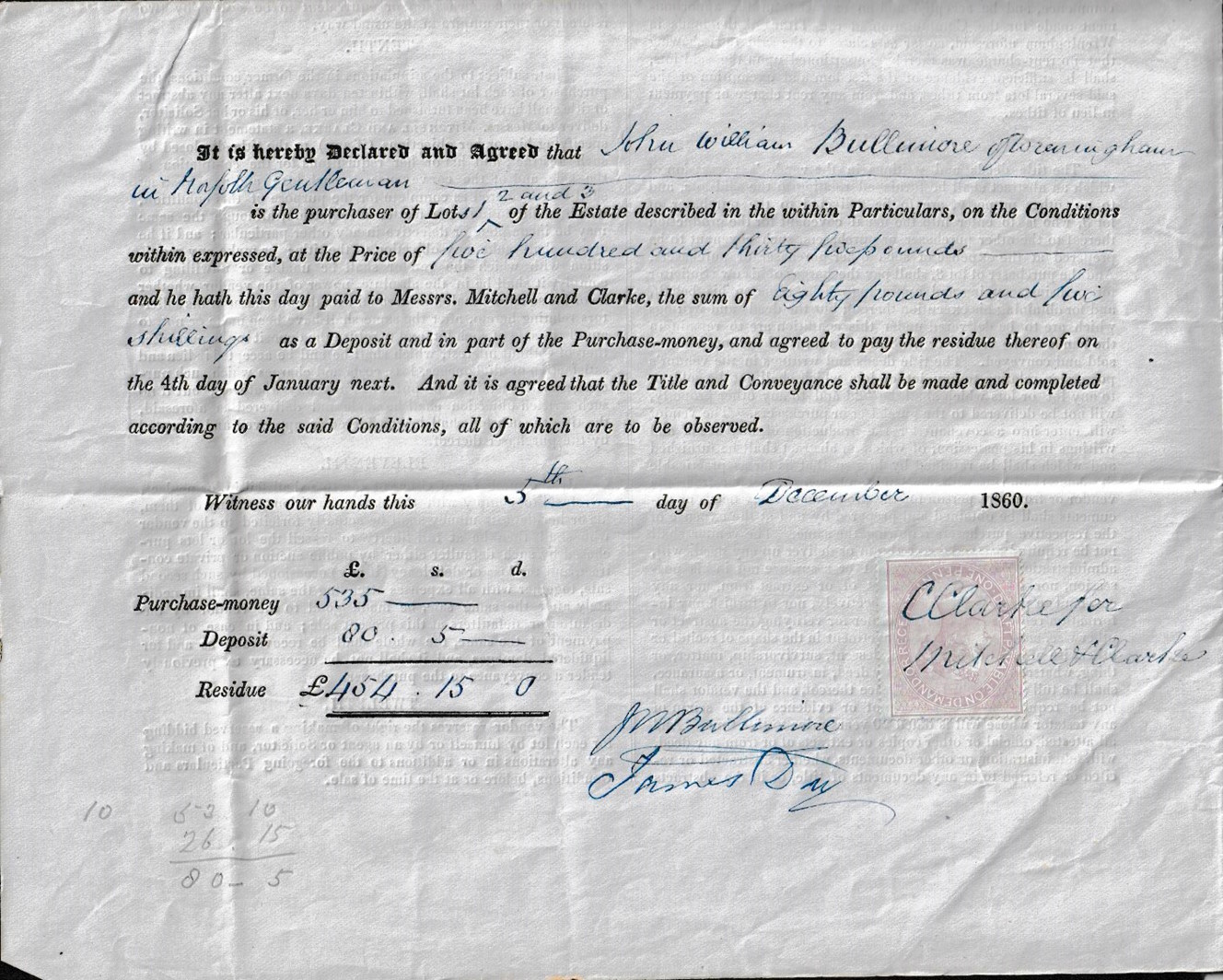

Becoming a Property Owner

In December 1860, John Bullimore bought property located in Ashwellthorpe Road – directly opposite Burton’s Farm. The acquisition took place at an auction at the Bird in Hand. The three Lots comprised: a single cottage, a double cottage and a 4 acre orchard.

It all belonged to James Day – who eventually passed away in March 1861. January 1861 found John Bullimore making the final payment to James Day through solicitor: Mr Clarke of Wymondham. On the 29th January, John Bullimore collected the deeds from Mr Clarke – and, whilst at the solicitor’s office, the diary tells us he made his Will!

Several days later, John Bullimore rode out to Morningthorpe where he bought four apple trees and a green sage from a Mr Goldsmith. The next week, he planted all of these in his new 4 acre orchard.

Step-Mother

In the early weeks of the 1861 diary, we learn that John Bullimore’s step-mother, Rebecca Bullimore (nee Sewell), was coming to the end of her days. Together with his sister, Anna, they visited their step-mother at a Bracondale property (belonging to a Miss Jemima Lindall, at Doman’s Buildings) on the outskirts of Norwich. [Believed to be No.8 Bracondale Green – information courtesy of the Bracondale History Group, June 2023]

On the 8th March, Rebecca died. Her funeral took place at St Mark’s Church, Lakenham on the 15th.

John and Anna’s birth mother had died within a year of John Bullimore being born in 1827. In the diary, he describes Rebecca variously as his “mother” and his “mother in law” although we would use the term step-mother, today.

Other Family Members

At different times during 1861, members of John Bullimore’s family members are described visiting Wreningham. They were generally hosted by his Aunt Denny at Hill Farm and usually entertained at Burton’s Farm, too.

Crop Planting

A separate surviving document from the period – also written by John Bullimore, lists the crops grown across the 3 farms. The listing starts in 1857 with the last crop details given in 1883. His crop information for 1861 is as follows:

| Wheat | 75¼ acres |

| Barley | 75 acres |

| Swedes | 40¼ acres |

| White Turnips | 9 acres |

| Beet | 23½ acres |

| Beans | 11 acres |

| Clover | 20½ acres |

| Black | 30¾ acres |

| Carrots | 1¼ acres |

In total, about 287 acres was in cultivation with the remaining 190 acres being in meadow.

The Harvest

Hay cutting got underway in July followed by the main part of the harvest running through to the end of August at a relentless pace.

The diary provides a huge amount of detail. This includes descriptions of individual crops taken from specific fields – often listing how many cart loads were transported and where each of them were stored across the three farms. Fortunately, the weather during the 1861 harvest appears to have been favourable. The multiple pages make clear how hard everyone must have been working. The final and simple words: “Harvest wages paid” which closed the entry for 31st August appears to speak volumes.

Of course, later crops such as beet were not harvested until October/November – by which time, the next year’s wheat was being set.

Steam-Threshing

At the start of the 1800s, the threshing of crops was still undertaken by hand. Horse powered threshing equipment soon became available and, by the 1840s, steam threshing equipment had been invented. The process was powered by portable steam engines; the term “portable” was used to describe these first mobile steam engines being pulled between farm locations by horses! Steam power resulted in much quicker and cheaper processing than the previous methods. Both the threshing equipment and the steam engine – with its specialists, were usually provided to farms as a visiting “contract” service.

Unlike today, when combine harvesters separate and collect the grain as they drive through the fields, the complete wheat and barley crop was cut in the fields and taken (with the grain still on the stalks) back to the farm. It was stored in stacks, covered by a straw thatch to protect the crop from rain, until there was the time and opportunity to carry out the threshing. The threshing then took place, at invervals, throughout the year.

The diary lists 14 days during 1861 when John Bullimore had engaged the threshing team and their equipment. During their various visits, they deployed to all of the three Wreningham farms depending on the location of the next stack.

The 1861 Census suggests that none of these specialist skills existed in Wreningham, at the time. However, John Bullimore’s farm labourers would have been heavily involved in feeding the crop into the thresher and then bagging up the grain, collecting the straw and chaff etc.

In 1861, the 14 days of steam threshing were spread over 7 separate visits to Wreningham.

Selling Grain / Trading Animals

John Bullimore appears to be selling his grain at the Corn Exchange in Norwich. The diary lists a number of the merchants with whom he traded by name: most of those same names can be found in Norfolk County Directories from the period.

A new Norwich Corn Exchange had been opened during 1861 replacing an earlier building which was no longer large enough – although there is no information about any of this in the diary.

The diary describes John Bullimore regularly trading livestock – both buying and selling, through a Mr C Huggins. This gentleman does not appear to have been a Wreningham resident.

National Events

Only two national events are mentioned in the diary but each was very significant.

The first was in June: it was a major fire in London. In due course, this event became known as the “Great Fire of Tooley Street” – with huge financial costs. The fire was along the south bank of the Thames, opposite the City of London, and it completely destroyed multiple warehouses and their extensive contents. It was too large to tackle in a meaningful way and burnt itself out after about two weeks.

The second event was the 14th December death and 23rd December burial of Prince Albert .

Easter and Christmas 1861

Both Easter (Good Friday – 29th March) and Christmas Day were celebrated at Burtons Farm. Each event involved hosting visitors. These were:

Good Friday: “Mr & Mrs Elvin, Mrs Wiffin, Aunt & Mrs Harris met at Miss Burtons”

Christmas Day: “Jas Head, Wm Elvin & wife, D Elvin, H Jackson, George Minns, Mrs Wiffen – C Fisher & wife – Mrs Denny [aunt] – here to dinner”

Two days before Christmas, the diary tells us that “Miss Thurston” [the Burton’s Farm house-keeper who John Bullimore eventually married] had sent her turkeys to “65 Lombard Street”. Interestingly, this was the address of the Norwich based Gurneys Bank, in the City of London. Were these turkeys sent via Flordon railway station to Liverpool Street? The diary doesn’t say. We may note: “express train” journey times of the period from Norwich to London were little different from those of today!!

In John Bullimore’s Pocket Book for the period, the first week of January 1862 shows that he paid Martha Thurston 8 shillings for a turkey; perhaps they had consumed this particular turkey for their Christmas Day dinner at Burton’s Farm? Was “8 shillings” also the “going rate” for the Gurneys Bank shipment (plus transportation costs etc) – or did the bank’s recipients pay a little more for each of theirs?