Napoleonic War Period. Each pattern from the 6 rotated

shutters (“visible” or not) provided part of a longer message.

The Wikipedia entry for Wreningham includes the words: “From 1808 to 1814 Wreningham hosted a station in the shutter telegraph chain which connected the Admiralty in London to its naval ships in the port of Great Yarmouth.” So, what is that all about?

In the late 1700s, a Frenchman, Claude Chappe, created a mechanical signalling system to enable messages to be relayed across great distances. This was achieved using articulated semaphore signalling arms mounted on towers. Each of the towers was manned – with an observer using a telescope to read the semaphore settings on a distant tower. He would call out the message to a colleague, standing next to him, who would display the same semaphore setting on their own tower for the next observer along the line to read etc. A continuous line of towers could relay a message hundreds of miles within minutes. The French made effective use of their signalling system during the French revolution when fast changing situations in distant towns required the fastest possible responses.

When Napoleon threatened to invade Britain, the Admiralty realised that a similar system would be a great asset. It would provide an effective way for Whitehall to achieve almost instantaneous communication with the naval ports – replacing a man on horseback carrying a note!

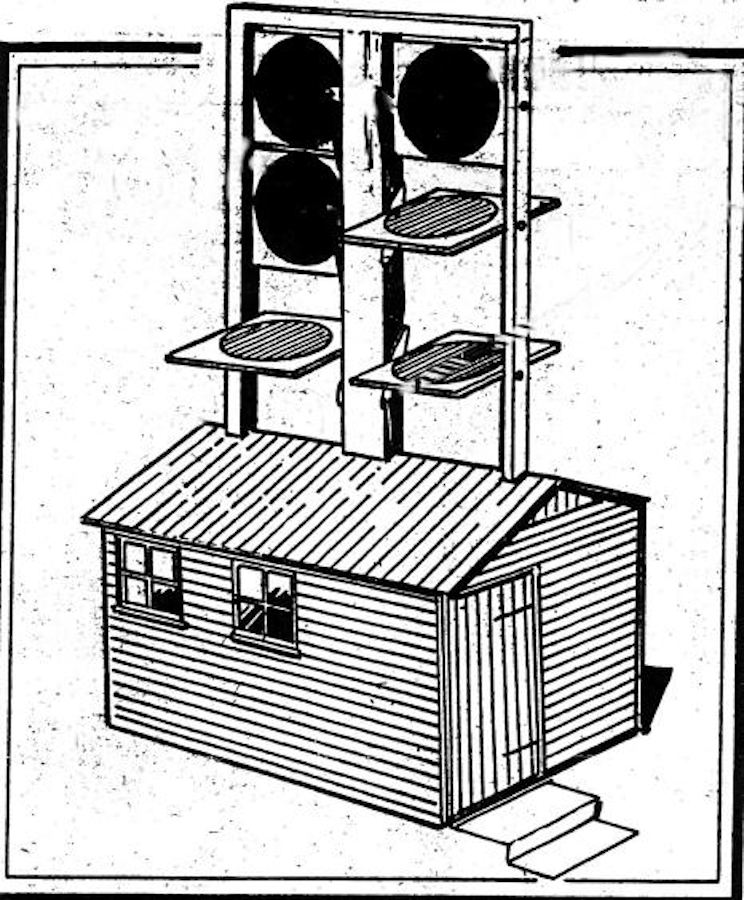

It was politically important for a British design to be different. The British (Admiralty) system, designed by George Murray, used 6 shutters in place of the French single semaphore arm enabling more complex messages to be transmitted, quickly. In short order, this Admiralty system was tested across Portsmouth harbour and proven to work. It became known as the “Shutter Telegraph”.

In this country we were also fortunate to have an optics specialist: John Dollond (son of an exiled Frenchman!), who had developed a method to vastly improve the effectiveness of telescopes – significantly increasing their useful range. The result was that our Shutter Telegraph stations could be separated by much greater distances than the earlier French semaphore stations. This provided further benefits; a line of British systems could be built faster and cost less money. Always important to The Treasury!

The Admiralty’s first full Shutter Telegraph line, connecting the Kent port of Deal with London, was designed and constructed within the space of 12 months – opening in 1796. The success of the Deal line resulted in funding being provided for a London to Portsmouth, opened in 1800, followed by a London to Plymouth line which opened in 1806.

Finally, a London to Great Yarmouth line was approved and funded. It was surveyed in 1807 and completed by June 1808.

One of the Telegraph Stations on this final line was situated in Wreningham. Records on the Great Yarmouth line are sparse but the Wreningham station was documented as being “near the church” – with the adjacent telegraph stations up/down the line being on the present-day water-tower location in Norwich and about 200m to the South East of the farmhouse at Telegraph Farm, Carlton Rode.

Over the years, the precise Wreningham location has been debated. The challenges have related to topography. Parts of our local terrain are relatively flat (but with subtle irregularities) and there are many more trees, today, than 200 years ago. These extra trees obscure what was once the sightline.

We started our investigation using 3D “GIS” software and the best quality terrain data we could find – needing it to be devoid of trees, vegetation and buildings. From this, we established that there is a small area near the southern end of Hethel Road (“near the church”) from where someone standing on the ground, would probably (once) have been able to see the Shutter Telegraph location in Norwich. However, the terrain in the opposite direction, towards Carleton Rode, was much more complex to assess. A alternative and easier approach was required.

By chance, a state-of-art online 3D terrain model (for the entire globe!) was discovered here. Trial and error experimentation with this online “package” conclusively proved that any “near the church” ground location, which could (probably) see Norwich, could definitely not see Carlton Rode. This latter limitation is due to a “shoulder” of land on the south side of Ashwellthorpe getting in the way. Other Wreningham ground locations which might have once been able to see Carleton Rode would never have been able to see Norwich – the topography doesn’t allow it in both directions from the same spot.

However, we also noted that both the St Albans and Great Yarmouth Telegraph Station shutter assemblies had been constructed on top of existing stone towers. At the time, local artists in those places had made drawings of the shutter assemblies on each of them. So how about this solution at Wreningham? The same online 3D terrain model confirmed the following answer: if the Wreningham shutter assembly was placed on the top of Wreningham church tower, the site-lines to both the Carton Rode and Norwich telegraph locations were easily achievable. This was probably how the early 1800s surveyors had determined the link was possible in the first place. It also suggests that “near the church” for the Wreningham station was probably referring to the “hut” which the operators used for their local accommodation. The nearby Bird in Hand pub (believed open in the 1790s) might have been useful, too!

Shortly before the suggested “answer” to our original conundrum about the Wreningham Telegraph Station location was “revealed”, a long-standing member of the Wreningham community told us:

“Ken Hanton (a Wreningham churchwarden for 22 years and who died in 2005) always believed the old Telegraph was on top of the church tower”

We then need to consider that Ken Hanton’s father, a Wreningham churchwarden for an earlier 28 years, was born in 1889. A little bit of village folklore, handed down through the generations? – and, perhaps, a story on the point of being lost!

Maybe the stresses and strains on the tower induced by these extra loads in the early 1800s led to the tower’s eventual collapse just over 35 years later? After all, until that point, the tower had been stable for hundreds of years.